Children In Aadversity

Common examples of childhood adversity include child abuse and neglect, domestic violence, bullying, serious accidents or injuries, discrimination, extreme poverty, and community violence.

How does a childhood adversity affect the brain?

Early adversity can lead to a variety of short- and long-term negative health effects. It can disrupt early brain development and compromise functioning of the nervous and immune systems. The more adverse experiences in childhood, the greater the likelihood of developmental delays and other problems.

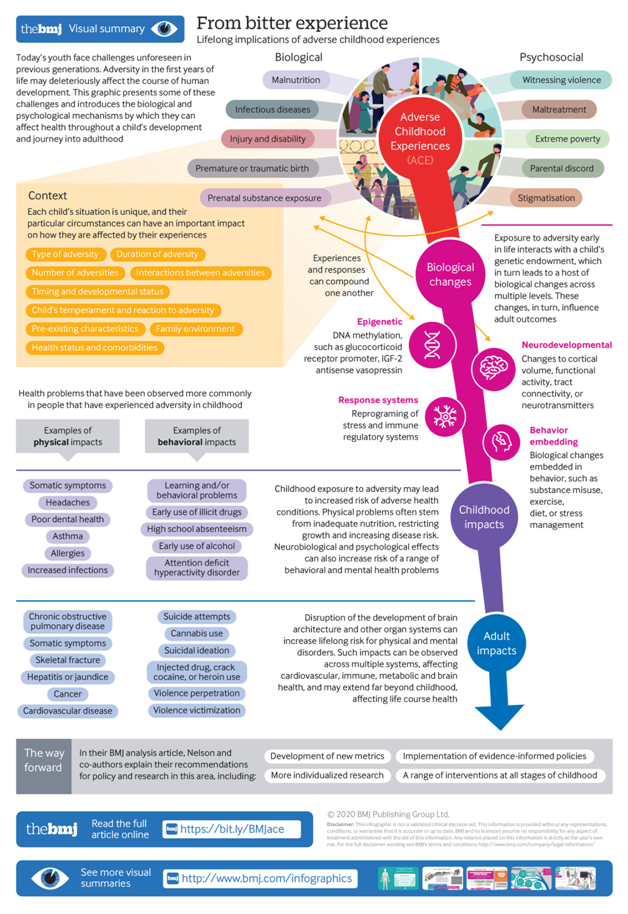

Exposure to adversity early in life interacts with a child's genetic endowment (eg variations in genetic polymorphisms), which in turn leads to a host of biological changes across multiple levels. These changes, in turn, influence adult outcomes). The prevalence of “toxic stress” and huge downstream consequences in disease, suffering, and financial costs make prevention and early intervention crucial.

Today’s children face enormous challenges, some unforeseen in previous generations, and the biological and psychological toll is yet to be fully quantified. Climate change, terrorism, and war are associated with displacement and trauma. Economic disparities cleave a chasm between the haves and have not’s, and, in the US at least, gun violence has reached epidemic proportions. Children may grow up with a parent with untreated mental illness. Not least, a family member could contract covid-19 or experience financial or psychological hardship associated with the pandemic.

The short and long term consequences of exposure to adversity in childhood are of great public health importance. Children are at heightened risk for stress related health disorders, which in turn may affect adult physical and psychological health and ultimately exert a great financial toll on our healthcare systems.

Growing evidence indicates that in the first three years of life, a host of biological (eg, malnutrition, infectious disease) and psychosocial (eg, maltreatment, witnessing violence, extreme poverty) hazards can affect a child’s developmental trajectory and lead to increased risk of adverse physical and psychological health conditions. Such impacts can be observed across multiple systems, affecting cardiovascular, immune, metabolic, and brain health, and may extend far beyond childhood, affecting life course health. These effects may be mediated in various direct and indirect ways, presenting opportunities for mitigation and intervention strategies.

Defining toxic stress

It is important to distinguish between adverse events that happen to a child, “stressors,” and the child’s response to these events, the “toxic stress response. A consensus report published by the US National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2019) defined the toxic stress response as:

Prolonged activation of the stress response systems that can disrupt the development of brain architecture and other organ systems and increase the risk for stress related disease and cognitive impairment, well into the adult years. The toxic stress response can occur when a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity—such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, exposure to violence, and/or the accumulated burdens of family economic hardship—without adequate adult support. Toxic stress is the maladaptive and chronically dysregulated stress response that occurs in relation to prolonged or severe early life adversity. For children, the result is disruption of the development of brain architecture and other organ systems and an increase in lifelong risk for physical and mental disorders.

What is childhood adversity?

A large number of adverse experiences (ie, toxic stressors) in childhood can trigger a toxic stress response. These range from the commonplace (eg, parental divorce) to the horrific (eg, the 6 year old “soldier” ordered to shoot and kill his mother. Adversity can affect development in myriad ways, at different points in time, although early exposures that persist over time likely lead to more lasting impacts. Moreover, adversity can become biologically embedded, increasing the likelihood of long term change. Contextual factors are important.

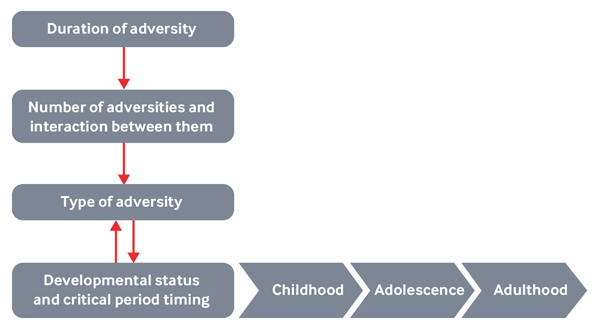

Type of adversity.

Not all adversities exert the same impact or trigger the same response; for example, being physically or sexually abused may have more serious consequences for child development than does parental divorce.

Duration of adversity

How long the adversity lasts can have an impact on development. However, it is often difficult to disentangle duration of adversity from the type of adversity (eg, children are often born into poverty, whereas maltreatment might begin later in a child’s life).

Developmental status and critical period timing.

The child’s developmental status at the time he or she is exposed to adversity will influence the child’s response, as will the timing of when these adversities occur.

Number of adversities and the interaction among them

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study and subsequent body of ACE research provide compelling evidence that the risk of adverse health consequences increases as a function of the number of categories of adversities adults were exposed to in childhood. Although this seems intuitive, it belies the fact that, when it comes to severe adversity (eg, maltreatment), few children are exposed to only a single form of adversity at a single point in time. In addition, the effects of exposure to multiple adversities are likely more than additive. Thus, multiple forms of adversity may act in complex and synergistic ways over time to affect development.

Exacerbating factors

Children with recurrent morbidities, concurrent malnutrition, key micronutrient deficiencies, or exposure to environmental toxicants may be more sensitive to the adverse effects of other forms of toxic exposures.

Supportive family environments

Children develop in an environment of relationships, and supportive relationships can buffer the response to toxic stress. Safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments are associated with reduced neuroendocrine, immunologic, metabolic, and genetic regulatory markers of toxic stress, as well as improved clinical outcomes of physical and mental health.

Pre-existing characteristics,

many of the adversities being considered are not distributed at random in the population. They may occur more commonly in children and families with pre-existing vulnerabilities linked to genetic or fetal influences that lead to cognitive deficits, Infants who are more vulnerable to adverse life events (eg, stigma) include those born very early (eg, at 25 weeks’ gestation) or very small (eg, ∠1500 g), those born with substantial perinatal complications (eg, hypoxic-ischemic injury), infants exposed prenatally to high levels of alcohol, or those born with greater genetic liability to develop an intellectual or developmental disability (eg, fragile X syndrome) or impairments in social communication (eg, autism).

Individual variation,

finally, children may have different physiological reactions to the same stressor. For example, boyce, has proposed that by virtue of temperament, some children (such as those who are particularly shy and behaviorally inhibited) are highly sensitive to their environments and unless the environment accommodates such children, the risk of developing serious lifelong psychopathology is greatly increased; conversely, some children thrive under almost any conditions.